FG FINE ART LTD

Santi Buglioni

Florence, 1494 - 1576

Santi Buglioni’s esteemed mastery of this type of artefact is most eloquently documented by the “ten vitrified earthen heads” that he executed in 1542, commissioned by the very sophisticated Duchess of Florence Eleonora di Toledo, consort of Cosimo I de’ Medici, as a gift to her father, the powerful Viceroy of Naples don Pedro de Toledo, destined to adorn the loggias of the elegant palace built in Pozzuoli between 1539 and 1541.

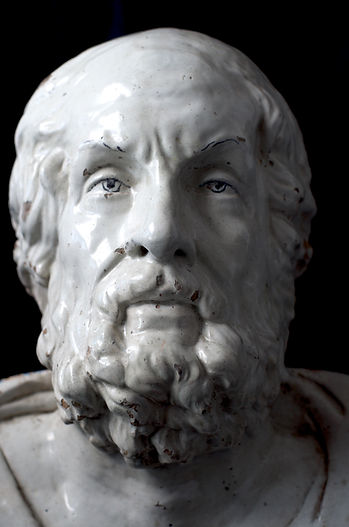

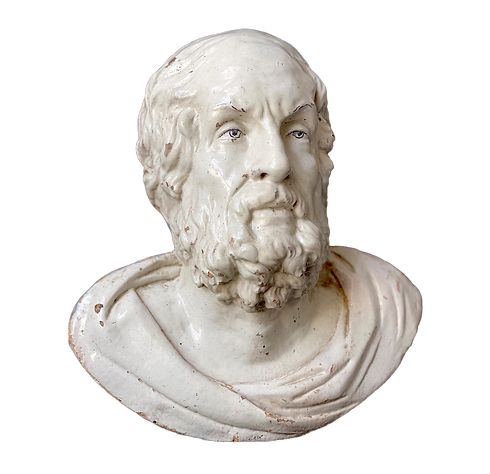

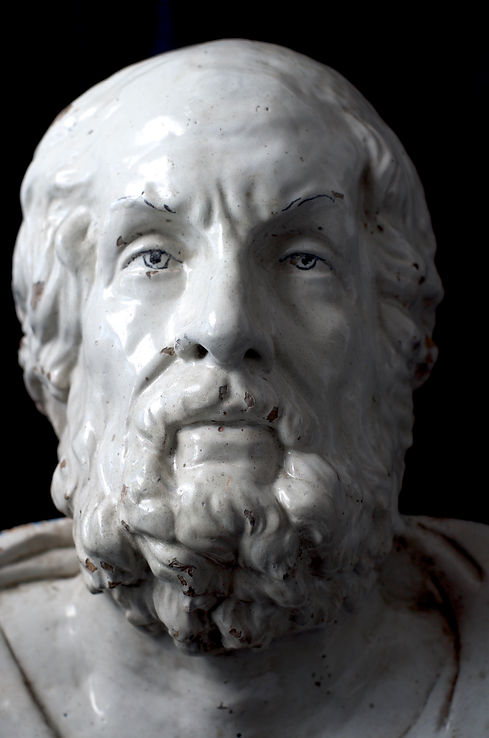

Bearded virile effigy “all’antica”: Ideal portrait of the poet Homer

Glazed terracotta, 40.5 x 37.5 x 16 cm

Provenance

Commissioned by Eleonora di Toledo in 1542 for Pedro di Toledo, Viceroy of Naples, for the Palace of Pozzuoli

Bibliography

Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Mediceo del Principato, 600, April 15, 1542, “Ricordi” del majordomo Riccio, 10R, 17R

B. Edelstein, Cultural exchange between Medici Florence and Vicereal Naples as reflected in Giovanni Antonio Nigrone’s Varii disegni, p. 162, in I disegni e i discorsi di Giovanni Antonio Nigrone «fontanaro ingegniero de de acqua», Vol. II, Rome 2024

Santi di Michele Viviani, known as Buglioni (Florence 1494 - 1576) was the nephew of Benedetto di Giovanni Buglioni (Florence 1459/60 - 1521), a resourceful sculptor whose style was influence by that of Verrocchio, established himself on the artistic scene in Florence and central Italy, between Rome, Perugia and Bolsena, around 1485 with his prolific production of glazed terracotta sculptures, similar in technical and typological aspects to those made by Andrea della Robbia - from whom, according to Vasari (1568), he would have stolen the “secret” of this art – even if characterised by a greater formal simplicity and an open eclecticism, which was appreciated by cultured and refined patrons such as Pope Innocent VIII and Cardinal Giovanni dei Medici, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent and future Pope Leo X. An art later inherited by Santi Buglioni and interpreted by him with more challenging and original, updated solutions in line with the taste of early Florentine Mannerism, as can be seen in the famous, glorious frieze depicting the Seven Works of Mercy in the portico of the Ospedale del Ceppo in Pistoia (1526-1528). Santi Buglioni is an artist, who also distinguished himself for his work in the Medici workshops often in collaboration with Tribolo, who shortly before his death would be remembered by Vasari (1568) as the “only one” still capable of “working sculptures of this kind”.

Thus, in the varied production of the Buglioni family, directed by a more sophisticated clientele, clypeated busts all'antica similar to those made in large numbers by the Della Robbia family from the 1460s onwards, such as, for example, the eighteen medallions with effigies of emperors and illustrious men made by Andrea in 1492 for the Aragonese villa of Poggioreale in Naples, of which only one very damaged example survives in the Capodimonte Museum, the sixty-six portraits of characters from the Old and New Testament, Fathers of the Church and Founding Saints of the main religious orders modelled in 1522-23 by his son Giovanni della Robbia for the Certosa del Galluzzo, or those of profane subject and marked antiquarian taste that by the brothers Girolamo and Luca “the Younger”, active at the court of François I of France, decorated the fabulous Château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne (1527-1564), the Château de Sansac (1529) and the Château d'Assier (1526-1535), one of which is now in the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

This solemn robed effigy, depicting a man with a receding hairline and a full beard, no longer young but still expressing a resolute intellectual and moral energy in the pensive, wrinkled features of his face, constitutes a significant unprecedented testimony to the role played by “memories of antiquity” in Renaissance portraiture: a genre to which critics have devoted increasing attention, also highlighting the importance of similar glazed terracotta busts made in the two family-run Florentine workshops that held a monopoly on this “secret” art, the Della Robbia and the Buglioni.

It is, in fact, an image taken from an ancient ideal portrait of Homer, the supreme Greek epic poet (8th century BC), which can be reconducted to the so-called “blind” type known today in more than twenty examples, mostly Roman copies of a lost Hellenistic Greek archetype, including the well-known marble herm in the Musée du Louvre in Paris from the Caetani Palace in Rome, purchased by Clement XII in 1733 from the Albani collection for the Capitoline Museum, requisitioned by Napoleon in 1797 and, after various vicissitudes, returned to France in 1815.

Moreover, a series of four glazed terracotta medallions with clypeated busts of illustrious characters projecting into garlanded frames, acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1864 in the Palazzo Guadagni in Florence, previously attributed to Giovanni della Robbia, and later rightly to the rival workshop of Benedetto and Santi Buglioni, can offer us more pertinent confirmation for the iconography of the work under examination. Busts that “clearly reproduce ancient portraits among which are clearly recognisable those of Octavian Augustus and Agrippa, considered “an undoubted glimpse into the consistency and appearance of the series of emperors and illustrious men that decorated the superstructures of Palazzo Medici” commissioned by Lorenzo il Magnifico “as political and moral models.

Eleonora di Toledo, daughter of Don Pedro di Toledo, the first Viceroy of Naples, arrived in Naples from Spain in 1534 when she was barely 12 years old and in Florence at the age

of 17 in 1539, and brought with her a remarkable cultural baggage derived from diverse sources.

Her role as patron of the arts is well known, it is enough to mention her important contribution to the creation of the Boboli Gardens and the decorations in the rooms of Palazzo Vecchio24, as well as her constant and continuous relationship with artists such as Vasari, Bronzino, famous his

portrait of her with the son Giovanni, and our Santi Buglioni.

The artistic bond between Eleonora and Santi Buglioni, one of her favourite artists, was very strong, consolidated perhaps thanks to the commission he received for the triumphal celebrations of her marriage to Cosimo I dei Medici: Santi Buglioni in fact helped Niccolò il Tribolo in the construction of a temporary equestrian statue of Cosimo’s father, Giovanni delle Bande Nere, later remembered by

Giorgio Vasari as the most beautiful artwork created for those wedding celebrations. Eleonora also commissioned to Santi Buglioni the flooring of the Grotticina in Boboli, in addition to that of the Sala di Leone X in Palazzo Vecchio.

Eleonora’s contribution to the artistic enrichment of his father’s residences in Naples, in particular that of Pozzuoli, was also notable. Following the terrible earthquakes in the

Phlegraean area that destroyed Pozzuoli and made it unliveable, in 1538 Don Pedro had built a palace, with a tower and protected by a moat, to redevelop the area with large gardens, which reached as far as the sea, the so-called “Horti toledani”, more typical of suburban villas than city residences, where the water that flowed from the fountains and irrigated the estate, cultivated with wheat and vines, was then channelled to a new public fountain for the use of

the population.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleonora di Toledo and his son Giovanni, detail,Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi

Girolamo Macchietti, Baths at Pozzuoli, detail,Florence, Palazzo Vecchio

It was in this context that Eleonora wished to donate ten terracotta heads to her father for his favourite palace, commissioning them from Santi Buglioni, an artist with whom she had a special bond.

News of the commission is preserved in the Medici Archives where payments made to Buglioni and his collaborator Marignolli are also recorded:

15 April 1542: [...] and was told to pay Marignolle three scudi for the heads of “earth” (terracotta). Made to be sent to the Viceroy of Naples […].

15 April 1542: [...] I made a policy to Michel

Ruberti to pay Marignolle and Santi Buglioni eight scudi for

the heads of “earth” (terracotta) to send to Naples […].

28 settembre 1542: [...] I made a subscription on

account of Marignolle and Santi Buglioni of twenty-five scudi for the ten heads of glazed terracotta for the duchess [Eleonora di Toledo] to send to Naples. Balance for Tribulo. To Michel Ruberti […].

The earthquakes that immediately followed in the area and the end of Spanish rule led to a progressive and inexorable abandonment of the Pozzuoli palace, which has now almost entirely disappeared, and to the dispersion of its furnishings

and works of art, with the sole exception of the Pierino da Vinci now in the Louvre and our Homer, the only one of the ten heads of Santi Buglioni identified to date.

Considering the fact that this is the only known virile bust that can be dated to Santi Buglioni’s mature and more refined phase, and that the only documented in the archives busts of this kind made by the artist are those commissioned by Eleonora di Toledo, it is easy to say, as Bruce Edelstein has recentrly suggested, the provenance of this one as part of that noble commission

A full fact sheet is available on request.